Youd Better Not Call Them Toys

George Murray wrote in The Live Steamer, March-April 1951

- Readers are advised to get a copy of the May issue of True magazine when it appears on the newstands late in April. It will have an extensive article and four pages of live-steam loco pictures and general interest about our live-steam hobby and live-steam tracks around the country. This man's magazine is recommended to readers and the article will give steam a boost.

You'd Better Not Call Them Toys

by Charles N. Barnard

True: The Man's Magazine, May 1951

There's a time coming when the steam locomotive may be as rare on American railroads as a Stanley automobile on today's highways. For a lot of people, this passing of the Iron Horse will leave a nostalgic absence of steaming thunder in the air that no sleek, silent, and damnedly efficient diesel engine will ever replace. But for about 6,000 men who lovingly and laboriously build steam-powered miniatures of today's mighty Hudsons, Atlantics, Niagaras, or Mallets, life will go on pretty much as usual. These are the "live steamers' - hobbyists extraordinary - and woe be to the uninitiated churl who looks over their track layout to ask if the engines run by electricity!

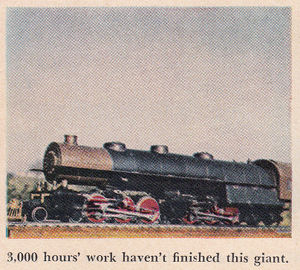

To build a live-steam scale locomotive requires between 1,000 and 5.000 hours of perfectionist machine and hand work that would make the mass producers of electric trains blush and watchmakers nod with a smile. Some builders have spent a lifetime on our engine; some have taken ten years; none has ever built one in less than twelve months. Hundreds of working parts go into these chugging, hissing little brutes. Each part is not only perfect to a given scale, but milled, turned, filed, or polished to a tolerance of a thousandth of an inch or less. Steam-pressure gauges work: so do Johnson bars, sand domes, brakes, water injectors, reverse gears, mechanical lubrication systems, electric generators, couplings. If you could take an honest-to-Casey-Jones engine and shrink it as a native shrinks a head, you'd have a live steamer's miniature.

It may be on forty-eighth the size of its prototype (1/4-inch scale) or one third (4-inch scale). It may burn coal, oil, or-rarely-alcohol; it may have enough power to haul two adults for eighty; it may be a Tom Thumb or a giant 4-6-6-4 Union Pacific. No matter its individual specifications, it represents one of the ultimate achievements of the model builder's art.

For the most part, the engines are judged on their performance and capacity to work (they will usually haul twelve to thirteen times their own weight) although appearance and meticulous attention to detail are admired as finishing touches. More important to the true live steamer are such factors as ratio of bore to stroke, ability to haul a load up a grade, springing and equalizing of the chassis, and such other minutiae as cab-controlled sand-boxes which actually spread fine grit on the tracks when brakes are applied, or steam-driven water pumps (or injectors) which keep the boiler full of water.

The result of all this is a locomotive-one which will stand still and pant steam in noisy gulps, pop off automatically when pressure gets too high, chug out great puffs of smoke and sparks in the approved manner, and respond to a hand on the throttle with a surge of surprising power.

Counted among the men who make live steaming a hobby are Walt Disney, James Melton, David Rose, King George of England, the late [Allan Roy Dafoe Dr. Dafoe] and more railroad executives than there are railroads. There are also bankers and clerks; machinists and dentists; postmasters and businessmen listed in the rolls. A live steamer can be anybody who loves a locomotive enough to build one.

Taken all together, they are inclined to be a highly sensitive clan. Love steamers consider themselves the elite-the graduate students-of model railroading and if there's anything that will make them blow their collective safety valve, it's a local reporter's story about Mr. Jones of the community who has a toy train and likes to play choo-choo. A second look at that "toy train" by any lover of polished brass and the machinist's art should be enough to understand the live steamers' sputtering anger.

Live steaming as an organized hobby began about seventy years ago in England-a country that has always been over-enchanted with the merits of steam power in general for the good reason that petroleum products for other forms of power are an expensive import. Britishers, from commoner to Royal Family, nurtured the hobby along, learning as they went. British model-craft magazines took it up and a locomotive engineer named L. Lawrence, writing under the initials L.B.S.C. (he worked for the London, Brighton & South Coast R.R.) soon became the outstanding purveyor of gospel on such subjects as how to install piston valves or the best way to tune a two-tone locomotive whistle. He's still at it and wherever live steamers gather in the world, you'll find them discussing what this expert calls his "words and music."

In the late 1920's, Americans became interested in the handsome little British miniatures that thundered on tiny rails and threw soot and cinders in the eyes of the engineers who rode on flatcars behind them. A Boston & Maine R.R> fireman named Charles A. Purinton of Marblehead, Massachusetts, may have been the first in this county to tackle the problem and build a miniature steam engine. If he wasn't the first, he was soon to become the L.B.S.C. of the U.S., anyway. In fact, it was at L.B.S.C.'s suggestion that Purinton organized the Brotherhood of Live Steamers in the late 1920's (Editors note: actually the BLS was formed in 1932). Today, this national organization has over 6,000 members and Purinton is still their leader.

Soon after the man from Marblehead built his first engine and outdoor track, interest in the hobby began to grow in interest in the hobby began to grow in the industrial towns of Massachusetts and New York. If Britishers had thought that Yankees lacked the necessary skill or patience for the job, they soon learned that a live steamer "across the pond" was no slob. Behold a character who one day gets himself a set of blueprints and maybe some rough castings and without even wondering if he'll live long enough, sets out to build himself a locomotive. There are several ways he can go about it.

He may buy blueprints from any one of several U.S. companies now supplying the live steam trade. Each of these outfits has the prints in stock for about a dozen engine types. They are available in a variety of scales, the most popular in the East being the 3/4-inch to the foot, or one sixteenth the size of an actual locomotive. ON the Pacific coast, 1-inch scale seems to be the rule. The same concerns may also sell the live steamer rough castings of wheels, cowcatchers, trucks, and a ready-to-install copper boiler complete with fire flues. But the builder has to take it from there. No company builds the finished product for sale.

Another type of live steamer is the one who buys only the blueprints and does the rest of the job "cut from solid," or stock steel, without benefit of castings. Probably the most courageous of all, however, is the "lone hand." This guy starts with a begged or borrowed set of actual locomotive blueprints (which, conveniently, are usually drawn in 1-1/2 inches to the foot scale or one-eighth size) and proceeds to adapt them. The lone hand may build an entire engine without knowing that anyone else has ever done such a thing. He may also make tragic mistakes that would have been avoided if he had worked along with the advice and comfort of some other live steamer.

No matter how a builder goes about it, the job isn't likely to cost him much in dollars and cents. An ex-piano tuner in Massachusetts recently built a handsome British Atlantic engine, right down to headlight lens, for $5 American. His friends called it Old Odds & Ends, but it runs like a thoroughbred. This is a Spartan example. Complete prints and materials for most models run about $75. Some, such as a Tom Thumb, cost as little as $25; a few of the more complex types, such as a Union Pacific 4-6-6-4 with two sets of independent drivers each on its own pair of cylinders, might run $150. Since the shop hours involved are considered recreation and a work of real devotion to the cause of live steam and hot cinders, labor is figured at $0.00 per hour. Aside from the original investment in a lathe (-inch swing recommended) and a drill press, live steaming is a frugal hobby.

Once finished-two words indecently used to describe the triumphant moment-a completed model reaches its day of mechanical puberty when fire is put into its boiler for the first time. The business of "firing up" is a ritual.

Boiler and tender tank are filled with water-tow to five gallons, depending on scale. The fire-box door is open and briquet coal that has been bathed in kerosene is shoveled in with a to-scale shovel. A match is tossed, door clanged shut, and an electric-powered blower, usually an old vacuum cleaner or the little woman's hair dryer, is fitted to the engine's stack to force a draft. This may also be accomplished by fitting a tire pump to the firebox. In five to eight minutes, steam pressure is up to 25 to 30 pounds per square inch. The blower is then removed and the engine's own steam-draft system takes over as on a full-scale loco.

With a good bed of hot coals on the grates, imported Welsh coal in thumb-nail size is shoveled in-or may be fed in by an automatic, steam-driven stoker. Operating pressure is about 100 pounds of steam with safety valves set to pop off at about 120. A new boiler is usually tested with 200 pounds of water pressure before it is steamed up.

Obviously, a locomotive with 100 pounds of steam in its guts and no track to run on is about as useful as a Patton tank in mid-Atlantic. Many of the builders have their own outdoor tracks (a few unorthodox alcohol burners run their trains indoors) but hundreds of live steamers now belong to some organized track with communal track facilities.

Rail for these tracks is supplied exclusively in the U.S. by Little Engines Inc., of Lomita, California. This company is also one of the leading suppliers of the hobby's other essential hardware. The rail is rolled to scale and anchored to creosoted cedar ties with to-scale, chisel-point railroad spikes. Some clubs elevate their track on trestles about three feet from the ground. California groups, however, usually lay their track right on the ground, ballasting the roadbed with crushed stone that is as close to scale as practical. The rails themselves may be either 8-pound (to the yard) iron mine rail or a Dural alloy. Old-timers in the game prefer the iron rail because, when slightly rusted, it provides better traction.

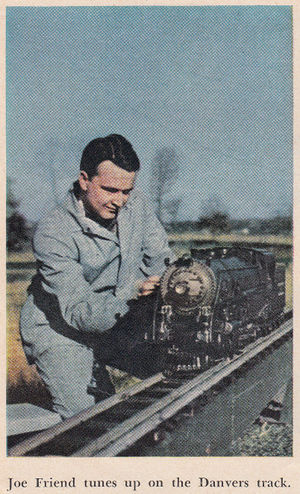

There are now about a dozen live-steam clubs from Massachusetts to California and in between. They welcome to membership anyone who builds live-steam miniatures, whether it be locomotives, steam traction engines, Stanley automobiles, or intricate stationary engines. The Golden Gate Live Steamers are at Oakland, California, with a new 1,300-foot track. Los Angeles has its Southern California Live Steamers with about ninety members and 1,000 feet of running track on the property of Little Engines. New York Live Steamers have their track at Wyandanch, Long Island. Eastern Live Steamers are at Hasbrouck Heights, New Jersey. Other clubs are fast growing in Chicago, Racine, Denver, Pittsburgh, and Reading, Pennsylvania. But it remains for the small New England town of Danvers, Massachusetts, home of the New England Live Steamers, to be one of the real hotboxes of activity in the U.S.

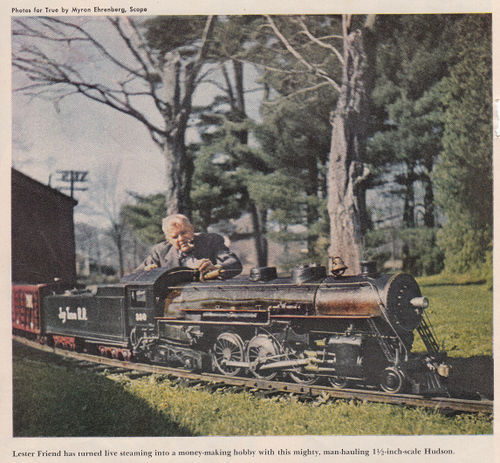

Danvers is twenty-two miles north of Boston and only a few miles from Marblehead, where Purinton built his first engine. Actually, there's nothing about the town to make it what many people call the live-steam captial of the U.S. except that a heavy-set, crinkle-eyed citizen named Lester D. Friend happens to own a cardboard-box factory there. Friend also happens to be an enthusiastic live steamer and long-time admirer of the pioneering Purinton.

Together, these two men organized the New England Live Steamers in 1936 and proceeded to build what was to become the longest model track in the world on the level ground behind Les Friend's box factory. The track now wanders and loops for nearly half a mile. Its trestle is fitted with two gauges of track for 3/4-inch and a 1-inch scale engines. Adjacent to the track is Yankee Shop, Les Friend's favorite enterprise and another leading supplier of the American live steamer's needs-whether they be prints, boilers, castings, or a good argument about steam versus diesel power.

Fifty-seven years old, Les Friend has been building live-steam models himself since the 1930s, when fellow members of the New England Model Railroad Society (electric) wagered he couldn't build an O-gauge (1/4-inch scale) engine that would run on steam power and pull one man.

As England's L.B.S.C. had done many years before, Friend took the problem home, lighted the aluminum-stemmed pipe that he calls his trademark, adjusted his beribboned pince-nez glasses, and took up a pencil. Several thousand hours and many months later, he brought a finished O-gauge locomotive back for the doubters to see. It smoked up the room, coughed, chugged, spit, and finally churned its tiny drivers into action. From that day on, Les Friend was a live steamer.

He's also been other things in his busy life. In his teens, Friend went west from New England to punch cattle, build houses, work in sash and door shops, and move with the harvests. The closest he ever got to a railroad was firing a dinky engine on a Southern Pacific R.R. construction gang in Oregon. It was probably at the Cadillac factory in Detroit that he finally settled down to being a master machinist-the kind of a man who fingers the bright metal of a newly turned piece and knows his micrometer won't be wrong.

Thanks to the prospering box business inherited from his father. Les Friend soon made the step from Cadillac factory to Cadillac. A good Rotarian, he considers this some sort of tribute to the American Way. It is also probably tribute to shrewd Yankee management, the talent for which Friend has in ample portion. Even as a live steamer, he has not overlooked the monetary advantages of the hobby for those quick enough to cultivate them. Hence, Yankee Shop.

Friend has three children and a wife, Juliet. His oldest son, Joe, 26, now manages Yankee Shop. Walter, 9, and Lana, 6, live in a kid's paradise of locomotives.

In one of the most handsome home shops that ever made one man jealous of another, the Friends-all of 'em-have built four live-steam models. Not long ago, Mrs. Friend drilled 6,000 rivet holes in the cab and tender of a Boston & Albany tanker. Lana has to stand on a box to operate the drill press. Walter, a bridge lover, is forever concocting some new scheme to make room for another bridge on the track.

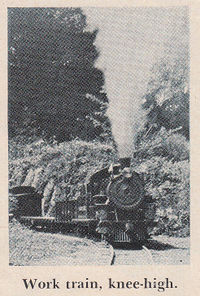

The Friends' models include a Tom Thumb in 3/4-inch scale which took 900 hours to complete; the B. & A. tanker, 2,000 hours; an unfinished 1-inch scale Atlantic with about 1,500 hours on her now; an unfinished Union Pacific Articulated that has consumed 3,000 hours; and a giant New York Central Hudson type in 1-1/2 inch scale. This engine heads up a model railroad kiddie ride at the Topsfield, Massachusetts, fair grounds. Called the Joytown Railroad, it is Les Friend's latest enterprise and has already hauled 38,000 squealing children in its first season (at three rides for 25 cents). Not one to overlook the transient dollar, Friend has hopes for enlarging the enterprise this year.

Once a year, on the first week end in October, Danvers renews its claim to live-steam eminence when the national Brother of Live Steamers holds its annual get-together at the N.E.L.S. track. Last year, several hundred members came from forty-two states and three foreign countries, bringing their beloved engines on special rigs fitted to the back seats or trunks of their automobiles.

Once at the track, they unite in a hive-like convention atmosphere, each avidly curious about what his friends have been building during the last twelve months. Those who have operating models take them to the steam-up shed at trackside where dozens of parking spurs feed into the main line. For those whose engines are unfinished, Yankee Shop itself is converted into a showroom. There, or at the track, the conversation is, logically, of one thing-live steam; gossip about the lone hand in California who took four years to build a handsome 3/4-inch scale Hudson only to find that he's used the wrong track gauge; about the two live steamers in Chicago who tried to operate on dry-ice power; about the increasing difficulty of getting the all-important Welsh coal that all live steamers use; about some magazine article that failed to distinguish between electric and steam models.

At trackside, they gather in knots to watch a newcomer's engine chug by on the main line; to clock a speeder at 26 m.p.h.: to make private wagers on how much drawbar pull such and such an engine will deliver; or to watch some lone-hand builder who is letting the fraternity see his locomotive for the first time. They talk in pairs and groups, quiet men with the hands of machinists making gestures that only another live steamer would understand. Once in a while, one will reach into his pocket to bring out some carefully wrapped, intricate part-maybe an injector cone or a set of piston rings-that hours of skill have gone to make.

By the time this week end is over, the live steamers have pumped each other of all the information they need; They've tested their engines, shown them off and recounted their problems to all who would listen; they've burned hundreds of pounds of the choice Welsh coal, turned hundreds of gallons of water into steam, and thoroughly investigated every tool drawer in Les Friend's shop to see what new gadgets he's using. Satisfied that all has been done that can be done to stimulate each other and the hobby for another year, they go home. The winter lies ahead-for some of them, a winter in which to start a new job; for others, a winter in which to finish one.

When they aren't attending conventions or working at their lathes, live steamers follow two periodicals religiously; the London-published Model Engineer, in which the venerated L.B.S.C. writes, and a beginning U.S. magazine, The Live Steamer, published by George Murray in Manchester, Connecticut. Both are packed with photos of new models, club news, classified and personal advertising, and intimate little notices about Tom Smith who has just fired up his 1-inch Niagara for the first time and is having trouble with his reverse gears. Shortly after that issue comes out, Tom will have a dozen suggestions or offers of help in his mailbox. Live steamers are like that.

The building of these miniature locomotives isn't entirely without its practical aspects beyond the pleasures the hobby affords its followers. Not long ago, Yankee Shop got an order from the government of Pakistan. The new Indian nation wanted on each Hudson, Atlantic, and B. & A. tanker for study in its Ministry of Transport. Yankee SHop shipped the goods and Pakistan built the engines. With their problems down to 3/4-inch scale, Pakistan knows what type of locomotive will do what and why.

A vocational school at Gaffney, South Carolina, orders a set of prints and castings every year from Yankee Shop. Members of its machine-shop class work on the engine as a group project, usually managing to get steam up by graduation in June.

Not long ago, Cecil B. DeMille called on Little Engines to provide him with a 1-1/2 inch scale miniature of an old-time circus train for use in his forthcoming motion picture, "The Greatest Show on Earth". Little Engines broke all precedent and had the finished engine built. It cost Paramount $5,000. When you see it in DeMille's picture, you'll never be able to tell it from P.T. Barnum's own. (See also One Inch Steam Locomotive Goes Hollywood)

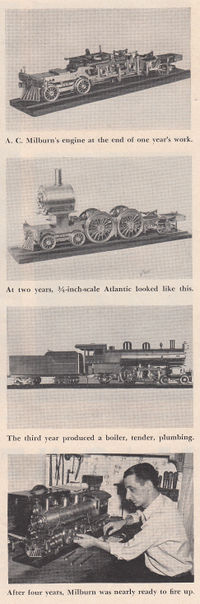

Many men who didn't know a drill press from a grape press until they started their first loco have found that the thousands of hours of trial-and-error shop work have made them competent machinists. One such is A. C. Milburn of Milford, Connecticut. Ten years ago he started work on a 1/2-inch scale freight engine in his spare time from a 4,000-foot coal shaft where he was a digger, today Milburn is a well-paid toolmaker-thanks to live steam.

It seldom happens, but occasionally a live steamer will sell an engine. He may be concentrating on a particular scale and wants to be rid of a larger or smaller model. When this happens, he may or may not find a buyer. Demand for the finished product is slim and when a sale is made, it is seldom for more than a few hundred dollars. George Murray, editor of The Live Steamer, is probably the only used-locomotive dealer in the U.S.

For commercial use in amusement parks, a Kansas company sells complete trains for about $6,000. These mass-produced models are approximately 2-1/2 inch scale, but are about as much like the real thing as a diamond is like a zircon. They look pretty, but underneath the shiny exterior lurk the mass-production touches of the profit-maker.

According to leading men in the hobby, there are about 1,500 completed live-steam locomotives accounted for in the U.S. today. Actually, there may be several times that number that have been built by quiet, modest guys who'd rather not have people come poking around their basement shops. There are several reasons for this beyond the fact that htey don't want to be misunderstood.

In the first place, a live-steam locomotive is never really finished and the builder of one is never so satisfied that he'll show it without some remark about work still to be done.

Take the man in Racine who was showing his engine to a friend.

"Beautiful scale model," the friend said.

"Well," allowed the live steamer, "it would be if I were a midget."

- Charles N. Barnard