The Rattle and Ruin Railroad

The Rattle and Ruin Railroad

by Ira D. S. Kelley

Mission, Kansas

The Miniature Locomotive, September-October 1954:

Relax, dreamers of railroad empire, and listen to the tale of a railroad that has not yet been built. In the telling you will hear of an interim project that you won't like and that doesn't conform. But, whether you like it or not concerns me not at all ... it suits me completely. So, you conformists, clip a coupon from your investment in model railroading and criticize the project to your heart's delight ... make as much fun of it as you like and then we'll all be content.

You see, it was thisaway ... Down on the farm in central Tennessee along about 1908 there used to pass our house every day a local passenger and a local freight train on the standard gauge Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis Railroad branch line from Dickens to the smelters of the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company. The crews used to stop and steal our peaches and apples and I used to toss ripe cantaloupes and tomatoes to the engineers as they passed. In return, could I help it if, once in a while, the passenger stalled on a hill and had to use sand to get rid of the soap some unknown youngsters had put on the rails? But this had nothing to do with some of the most perfect wrecks I have ever seen towed back for salvage or the scrap heap about twice each year.

With this example for incentive I went to work on my own railroad. But there were no beautiful kits on the shelves of our general store. Nor could I figure out how to use the brass bases of shot gun shells as car wheels. So, with the tools and materials available in the farm workshop, there appeared a string of cars the like of which should never hope to see. The wheels were wooden spools from Mother's sewing basket cut in half and mounted on nails for axles. The couplings were bent nails and fence post staples. And the equipment could not have produced without tin cans. Down behind the barn there appeared a cut which dropped my one and only track, consisting of wood strips for rails nailed to boards, to water's edge of the horse pond and out to its center on a beat-up dock. There being five critical brothers, the line promptly was dubbed The Rattle and Ruin Railroad, a name that I still retain in memory of those early days.

But then my parents moved to Kansas and the Tennessee railroad empire passed into oblivion. Out in Salina, Kansas, there soon appeared in our basement an inclined railway supported on brackets from the concrete wall and descending to a sharp curve around the ash pile. I was never able to afford an electric motor to propel the model open-air street car back up the include.

Then came high school, World War I service and college, which opened the door just a crack to expose the vast store of knowledge of which most of us may explore only a small portion in a life time. New horizons appeared with new goals to be attained ... one of which was to design and build from scratch in my own shop a live steam locomotive, rolling stock and trackage of such size and extent as to required a machine shop, a pattern shop, a cupola and foundry, stations, yards, signals, bridges and maybe a tunnel. But the necessity of earning a living and the fact I was handed a sheepskin reading "Civil Engineer" instead of "Mechanical Engineer," prevented more than a dream for future attainment. Also, heart trouble intervened ... the kind that induces otherwise sane people to get married instead of building railroads. So I married the girl and made my investment in a family instead.

As the first two boys began to grow up and were followed by tow more, it seemed to me that their lives not be complete unless they were introduced to be joys of model railroading. But the life of a civil engineer does not lead to permanence of location and, by the time the boys were of high school age, it required the fingers of both hands three times around to count the number of moves made. And nine years of extended active duty during and after World War II did not serve to advance the day when I could pull steam behind my own locomotive. But that service did conclude with three years' duty in my home town of Topeka, Kansas, where I once again began to dream and plan for that light railroad to be built before I grew whiskers to my knees. Also the presence of certain reserve officers in the office of the chief of motive power for the Santa Fe Railroad helped to increase my files of information for later use.

So I built a work bench, bought tools and even invested in a metal turning lathe. A copy of the Locomotive Cyclopedia furnished a wealth of information but nowhere could I find adequate information on actual methods of design. So, in order to interest the boys in the hobby, I compromised on O gauge and built my first kit, a wood reefer. That called for another and a stretch of track in the attic. Whereupon my sons discovered what beautiful wrecks could be produced by crashing these cars together. And did the hobby take? O yeh! They were all bitten by the model aviation bug and produced flying models far surpassing any railroad kit I ever assembled.

And so it came to pass, being left on my own with the wreckage of two kids, I bought a few more kits and some steel rail for a stretch of track over the workbench just under the basement window. But what good is a track that goes nowhere? So I bought enough more rail to produce trackage to (1) go over the canned goods shelves, (2) hang from the floor joists, (3) cross the side door entrance at grade, (4) go through the coal bins on a spiraled super-elevated curve, (5) miss the gas meter and (6) connect with the work bench trackage to complete a track that went somewhere and returned.

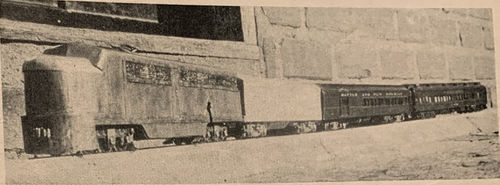

But what good is trackage without motive power? The catalogue provided convincing evidence that I could not afford to buy locomotives. So I built my own. On each end of a drop-center flat car casting I mounted an electric motor with its shafts projecting through the floor. On this shaft I mounted a worm gear meshed with a spur gear on the axle of the center pair of wheels of a six wheel truck. By sprockets and chain, power was distributed to all twelve wheels. A hand reversing switch was installed to reverse the direction of flow of electricity through the fields and thus reverse the direction of travel. And over the whole thing was placed a laboriously soldered sheet tin case suggesting that it was supposed to be a diesel-electric locomotive. I have yet to stall this locomotive. A tinplate transformer hooked to two-rail power transmission gave me the essential ingredients for many hours of enjoyment around the track. And what spectacular wrecks! Brother, when a sleek Pullman takes a nose-dive to the concrete floor, it takes more than back-shopping to repair the damage.

But have you ever known a model railroader who was completely satisfied? Shucks, I had scarcely scratched the surface. A few measurements indicated that a little chiselling of the brick foundation wall would result in access to the whole outdoors. And so The Rattle and Ruin Railroad extended service to new customers around the cistern, past the back porch steps, around the house, under the front porch and return along the side entrance. Running a train out of the basement was easy -- just turn on the juice and run like hell to get outside before she derailed somewhere. But running her back was sumpin, brother. It's a marvel Uncle Same did not have the job of fixing up a broken leg from the dash down those basement steps required to shut off the juice before No. 9 ran out of track.

But let's get serious for a while. Having spent one summer figuring out actual railroad alignment ahead of new steel, I was interested in trackage. But I had little patience with details ... I wanted yardage. So I bought wood batten strips, more steel rail, and assembled standard length track sections 18 inches and 36 inches long. All curves were spiraled and super-elevated so that 72 inches of track was required to pass through exactly 90 degrees. Similarly turnouts were designed without regard to the standard series of frog numbers but rather in order to use exactly 18 inches per turnout. And I remain non-conformist in that I still curve switch points. Aside from that, I compute trackage as for standard gauge and simply reduce the results to O gauge.

Steel rail I find is difficult enough to keep free of grime and rust indoors but is almost hopeless for use outdoors due to rust. So I bought aluminum rail for outdoor use. However, a white oxide forms on aluminum and I found that only 24 hours exposure without use required the rail heads to be sanded before electricity would reach the locomotive. This aluminum rail came in 48 inch lengths which suggested a new series of standard lengths. So now spirals are 24 inches long and straight and curved sections are 48 inches long so that two spirals and two curves will pass through exactly 90 degrees. Rails were spiked to batten strips. The strips were painted or creosoted. Nails were driven through these strips for anchorage and the strips were laid in cement mortar shaped like a railroad fill.

But military service ended and, since that time I have moved five more times. The railroad empire was salvaged and relegated to storage. But once again it appears that I am settled for awhile and the railroad empire is again taking form in the back yard -- all outdoors this time, rusty rail and all. Many hours have been puzzling out cab control, panel construction, yard layout, amperage required, and the minutia or detail required for a completely electric installation. The conclusion is rapidly crystallizing that there will be no less work and expense involved if I forget the whole idea of electrification and to to live steam -- yes, in O gauge. Thus iron and aluminum oxide will not have to be sanded off daily. But before I do that, with the help of one of those early day wreckers new turned mechanical engineer, I want to produce a power unit with a water cooled, gasoline engine driving an electric generator charging into a storage battery driving under frame electric motors built integrally with the trucks to provide power on every pair of wheels and walk away with not less than fifty cars, provided I can ever afford to buy that many.

So what about that 1-1/2 inch per foot light railroad? No sir! it is not forgotten. Some of these days I'll retire and then, brother, watch me go. Only trouble is I may have lost the urge by then and I'll need a ten acre farm with a stream through it, with hills and timber, before I'll be satisfied. But a man can dream can't he? O.K. then ... before I have whiskers to my knees I will build that railroad and pull steam behind my own locomotive while I walk away with a string of 50 neighborhood kids for a trip to Utopia and return. The difficult, in good engineering tradition, I have done immediately ... the impossible will take a little longer.

1940 Census

Ira D. S. Kelley was found on the 1940 US Census.

- Age: 40, born abt 1900

- Birthplace: Illinois

- Home in 1940: 1260 Mulvane, Topeka, Kansas

- Wife: Mildred C Kelley, age 40

- Son: Robert C Kelley, age 14

- Son: G David Kelley, age 13

- Son: William E Kelley, age 8

- Son: James W Kelley, age 7