Bill Michaels: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (12 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

[https://www.chaski.org/homemachinist/viewtopic.php?f=8&t=109746&start=36 Steve Bratina posted on <i>Chaski.org</i>]: | [https://www.chaski.org/homemachinist/viewtopic.php?f=8&t=109746&start=36 Steve Bratina posted on <i>Chaski.org</i>]: | ||

: I would say that was built by Bill Michaels of Racine Wisconsin. It was for sale a few years back on one of the sites. If you can find the November 1948 Model Railroader, the story about Bill, his engines and his chum Walley | : I would say that was built by [[Bill Michaels]] of Racine Wisconsin. It was for sale a few years back on one of the sites. If you can find the November 1948 Model Railroader, the story about Bill, his engines and his chum [[Wallace Ribbeck|Walley Ribbeck]] is in there. Walley's Hudson is in a case at the Tennessee Valley Railroad in Chattanooga. The picture in the magazine shows Walleys engine running with a B&O tender. He eventually built a NYC PT type tender for it. | ||

I also think Bill took this engine to Danvers when they still had 1/2" track. | |||

: I also think Bill took this engine to Danvers when they still had 1/2" track. | |||

<gallery widths=300px heights=300px perrow=2> | <gallery widths=300px heights=300px perrow=2> | ||

File:BillMichaels 2.5 Hudson 1.jpeg | File:BillMichaels 2.5 Hudson 1.jpeg | ||

File:BillMichaels 2.5 Hudson 2.jpeg | File:BillMichaels 2.5 Hudson 2.jpeg | ||

</gallery> | |||

== Model Railroader == | |||

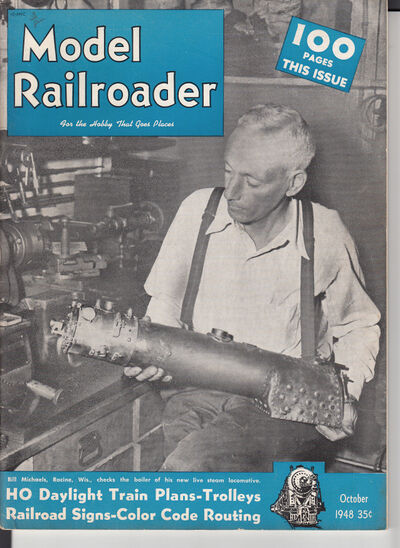

[[Bill Michaels]] appeared on the cover of [[Model Railroader]] October 1948. | |||

[[File:ModelRailroader Oct1948.jpg|thumb|center|400px|Bill Michaels inspects a live steam boiler. Cover page of Model Railroader magazine, October 1948.]] | |||

A three page story appeared in November 1948, as follows. | |||

'''Life of a Live Steamers''' | |||

''It's lots of work, lots of fun, and you ride with your engine'' | |||

By John Page, Editor | |||

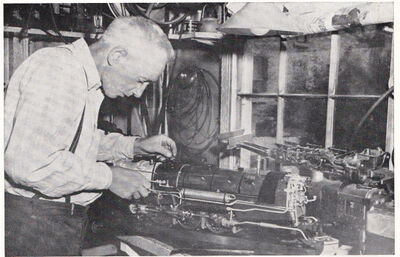

[[File:BlllMichaels Hudson ModelRailroader Oct1948 0001.jpg|thumb|right|400px|Bill's Hudson as it neared completion in his shop. Tank under running board is the whistle. Other live steam engine and mainframe are seen nearby.]] | |||

Sooner or later almost all of us hanker to own and operate a live steam locomotive. There is something very enthralling in the idea of owning a big, rugged live steamer powerful enough to haul us and several of our friends regally ensconced on trailing flat cars. But surely there is more to this branch of the hobby than a ride. | |||

To ascertain the exact nature of the live steam lure, and to learn some of the matter-of-fact objectives that must be accomplished if one is to become a live steamer and, incidentally, to satisfy a powerful yearning to run one of the steamers ourselves, we spent a beautiful autumn Saturday with [[Bill Michaels]] of Racine, Wisconsin. | |||

Bill was introduced to live steam back in 1908 when he began operating live steamers built by his father. Now a retired machinist, he has been building his own engines since 1927 when he built his first, a 4-4-2. | |||

Just in case you don't already know, a live steam locomotive is a miniature locomotive that is propelled by steam generated in its own boiler. Live steam model railroading, like conventional model railroading, consists of the building and operating of railroad models, but beyond that common premise there are wide dissimilarities between the two branches of the hobby. | |||

Chief difference is that live steamers build a model to operate <i>just it</i>, while conventional model railroaders build an engine to operate it <i>as part of a model railroad</i>. To the live steam model railroader, an engine is the end in itself. In contract, the conventional model railroader usually regards his engines as a means to an end, the end being the operation of a miniature railroad having complete prototype trains, traffic, and locate. | |||

Another notable difference is in how time is spent. For example, Bill thinks nothing of devoting 2500 to 3000 hours over a period of years to completing one locomotive, or about 10 times the 250 to 300 hours it takes a skilled modelbuilder to construct an electrically propelled engine. But, as Bill observed, an electrically driven model need only look like a locomotive; the live steam locomotive has to be one. | |||

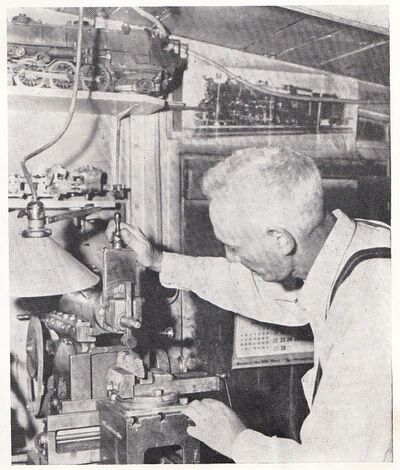

[[File:BillMichaels MachineShop ModelRailroader Oct1948 0003.jpg|thumb|right|400px|Removing some excess metal from a tender truck side frame. A B&O Pacific is partly visible above.]] | |||

Another noteworthy difference is that the live steam model railroader rarely builds any rolling stock other than a flat car to ride on, nor does he worry about his "scenery." It is created for him free of charge by that greatest of all diorama artists - Mother Nature herself. But while the live steamer doesn't have to contend with the electrical headaches that beset most conventional model railroaders, he is plagued by a different and equally difficult set of woes involving lubrication, capricious valves, flue troubles, and the like. | |||

You have doubtless heard that building live steam models is a technically exacting pursuit requiring many skills and a relatively heavy tool investment. That is precisely the truth. Bill has about all the power and hand tools that you would find in a small, well-equipped, commercial machine shop. He figures their value at about $2000. | |||

First thing Bill does toward building an engine is to draw a set of modified plans, usually based on prototype drawings in the <i>Locomotive Cyclopedia</i>. Modifications of prototype proportions are inevitable, for operational considerations require that driver tires be made wider, valve gear a trifle heavier, and cylinders a bit longer (a scale piston would be too thin). Also, side and main rods are made heavier and wheel flanges deeper. Nor, obviously, can such accessories as water and pressure gauges, control levers, and functional piping be held strictly to scale proportions. Slide valves are used at the cylinders instead of piston valves, although the cylinders have piston value outline. | |||

Bill makes the patters for drivers and cylinder block and has these parts cast at a local foundry. Some live steamers purchase driver and cylinder castings, but Bill enjoys his own pattern making. | |||

His practice is to build the chassis first, then the boiler, and finally the tender. Some live steamers make the boiler first. It's simply a matter of personal preference. | |||

Bill has an NYC Hudson, a B&O Pacific, and a free-lance Pacific in operation. Another Hudson, a free-lance Atlantic, and a 2-10-4 are under construction. All are to 17/32 inch scale, 2-1/2 inch gauge. Each engine costs him about $75 for steel and brass bar and sheet stock, copper tubing, etc. A Bassett-Lowke pressure gauge is the only commercial part he uses. The locomotives weigh from 70 to 85 pounds, including the tender. His Hudson weighs 55 pounds without tender and develops a drawbar pull of about 12 pounds, more or less. Wet or rusty rail is more slippery than dry, bright rail. | |||

The engines operate at steam pressures of 80 to 110 pounds. Fire is started with gasoline-soaked charcoal. After this is burning, pea-size bituminous coal is used for fuel. It is put into the firebox by a miniature shovel. Pistons are lubricated by an oil pump powered by the valve motion. | |||

Most live steamers use an automobile tire pump for forced draft to get steam up. Bill and his crony, [[Wally Ribbeck]], save their energy by using pressure obtained from Wally's Nash by removing a spark plug and attaching a hose that reaches to the locomotive. When steam pressure reaches 20 pounds, the locomotive's own blower can provide the necessary draft. | |||

A hat-full of coal will ield power for a day of operation, but the thirsty little engines need about a gallon of water per hour. Tap water is used. It is fed from the tender to the engine either by the injector, by a pump working off the front driver axle, or by a hand pump on the tender. | |||

Prior to injection into the boiler water is pre-heated in a copper coil that encircles the smokebox interior. The engines' copper boilers are patterned after the prototype, having flues, a combustion chamber, firebox syphons, etc. The boiler is fabricated with rivets and silver solder, and is tested before use with water at twice the steam pressure it will have to withstand. Live steam at 110 pounds pressure is not to be trifled with. | |||

Like regular model railroading, live steaming, in one or another of its ramifications, is a year-around affair. Bill does most of his construction work during the long Wisconsin winter in the workshop adjacent to his home. Summertime is primarily devoted to operation. Each Sunday (and many Saturdays) when the weather is favorable, Bill and Wally load their engines into their automobiles and head for the layout, which is on Bill's 3 acre tract of land located about 5 miles from his home. | |||

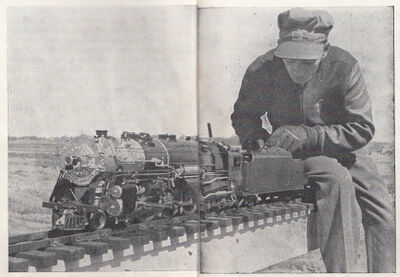

[[File:BillMichaels OperatingHudson ModelRailroader Oct1948 0002.jpg|thumb|right|400px|Bill operates tender hand pump to replenish boiler water. Note throttle handle projecting above the roofless cab.]] | |||

About 500 feet of the proposed 900 feet right of way is complete. Rail consists of 1/4 inch by 1/2 inch mild steel bar installed on trestle work to permit the engineer and his passengers to ride "side-saddle" with their legs dangling. | |||

Engine cab roofs are removed during operation to permit access to the throttle and reverse levers installed on the backhead. The engines are equipped with steam brakes which Bill rarely uses, preferring to retard or stop his engines by grabbing the trestle work with his free hand. | |||

How fast can they go? Well, Wally has timed his Hudson at about 10 miles per hour actual speed, or about 220 miles per hour scale speed. | |||

The pleasure of constructing a live steam engine needs no explaining to anyone who loves to build models. And the plaesures of operation? Ah, have you ever sat behind one of these chugging little iron horses and felt its powerful surge as you eased back the throttle? Ever get a good whiff of its warm, aromatic exhaust smoke mixed with fresh, hay-scented air? Ever looked own at the hypnotic driver and rod motion, or opened the firebox door to watch the tiny inferno raging? | |||

Until you've done these things, you will really never know why a man will devote 3000 hours, $2000 worth of tools, and all his Sundays to building and operating the 55 pounds of hot, oily temperamental machinery that is know as a live steam model locomotive. | |||

<gallery widths=300px heights=300px perrow=2> | |||

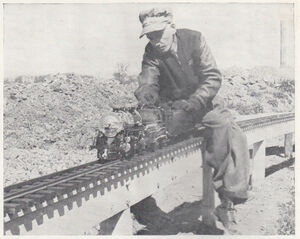

File:BillMichaels Engineer ModelRailroader Oct1948 0004.jpg|Steam's up and clear track ahead. Sensitive throttle will spin drivers if not skillfully handled. | |||

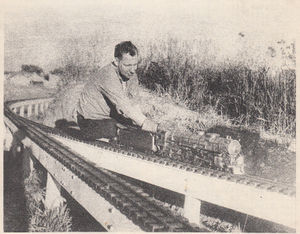

File:WallyRibbeck ModelRailroader Oct1948 0004.jpg|[[Wallace Ribbeck|Wally Ribbeck]] at the controls of his Hudson. Wally's automobile furnishes blower air to start fires in his and Bill's engines until engines' blowers take over. | |||

File:WalterRiddick Hudson RacineWisconsin 1949.jpg|Photo taken at the track of [[Bill Michaels|William Michaels]] of Racine, Wisconsin and shows [[Wallace Ribbeck|Walter Ribbeck]] of Kenosha with his fine 1/2 inch scale Hudson. From <i>[[The Live Steamer]]</i>, Jan-Feb 1950. | |||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

Latest revision as of 23:03, 27 September 2020

Steve Bratina posted on Chaski.org:

- I would say that was built by Bill Michaels of Racine Wisconsin. It was for sale a few years back on one of the sites. If you can find the November 1948 Model Railroader, the story about Bill, his engines and his chum Walley Ribbeck is in there. Walley's Hudson is in a case at the Tennessee Valley Railroad in Chattanooga. The picture in the magazine shows Walleys engine running with a B&O tender. He eventually built a NYC PT type tender for it.

- I also think Bill took this engine to Danvers when they still had 1/2" track.

Model Railroader

Bill Michaels appeared on the cover of Model Railroader October 1948.

A three page story appeared in November 1948, as follows.

Life of a Live Steamers

It's lots of work, lots of fun, and you ride with your engine

By John Page, Editor

Sooner or later almost all of us hanker to own and operate a live steam locomotive. There is something very enthralling in the idea of owning a big, rugged live steamer powerful enough to haul us and several of our friends regally ensconced on trailing flat cars. But surely there is more to this branch of the hobby than a ride.

To ascertain the exact nature of the live steam lure, and to learn some of the matter-of-fact objectives that must be accomplished if one is to become a live steamer and, incidentally, to satisfy a powerful yearning to run one of the steamers ourselves, we spent a beautiful autumn Saturday with Bill Michaels of Racine, Wisconsin.

Bill was introduced to live steam back in 1908 when he began operating live steamers built by his father. Now a retired machinist, he has been building his own engines since 1927 when he built his first, a 4-4-2.

Just in case you don't already know, a live steam locomotive is a miniature locomotive that is propelled by steam generated in its own boiler. Live steam model railroading, like conventional model railroading, consists of the building and operating of railroad models, but beyond that common premise there are wide dissimilarities between the two branches of the hobby.

Chief difference is that live steamers build a model to operate just it, while conventional model railroaders build an engine to operate it as part of a model railroad. To the live steam model railroader, an engine is the end in itself. In contract, the conventional model railroader usually regards his engines as a means to an end, the end being the operation of a miniature railroad having complete prototype trains, traffic, and locate.

Another notable difference is in how time is spent. For example, Bill thinks nothing of devoting 2500 to 3000 hours over a period of years to completing one locomotive, or about 10 times the 250 to 300 hours it takes a skilled modelbuilder to construct an electrically propelled engine. But, as Bill observed, an electrically driven model need only look like a locomotive; the live steam locomotive has to be one.

Another noteworthy difference is that the live steam model railroader rarely builds any rolling stock other than a flat car to ride on, nor does he worry about his "scenery." It is created for him free of charge by that greatest of all diorama artists - Mother Nature herself. But while the live steamer doesn't have to contend with the electrical headaches that beset most conventional model railroaders, he is plagued by a different and equally difficult set of woes involving lubrication, capricious valves, flue troubles, and the like.

You have doubtless heard that building live steam models is a technically exacting pursuit requiring many skills and a relatively heavy tool investment. That is precisely the truth. Bill has about all the power and hand tools that you would find in a small, well-equipped, commercial machine shop. He figures their value at about $2000.

First thing Bill does toward building an engine is to draw a set of modified plans, usually based on prototype drawings in the Locomotive Cyclopedia. Modifications of prototype proportions are inevitable, for operational considerations require that driver tires be made wider, valve gear a trifle heavier, and cylinders a bit longer (a scale piston would be too thin). Also, side and main rods are made heavier and wheel flanges deeper. Nor, obviously, can such accessories as water and pressure gauges, control levers, and functional piping be held strictly to scale proportions. Slide valves are used at the cylinders instead of piston valves, although the cylinders have piston value outline.

Bill makes the patters for drivers and cylinder block and has these parts cast at a local foundry. Some live steamers purchase driver and cylinder castings, but Bill enjoys his own pattern making.

His practice is to build the chassis first, then the boiler, and finally the tender. Some live steamers make the boiler first. It's simply a matter of personal preference.

Bill has an NYC Hudson, a B&O Pacific, and a free-lance Pacific in operation. Another Hudson, a free-lance Atlantic, and a 2-10-4 are under construction. All are to 17/32 inch scale, 2-1/2 inch gauge. Each engine costs him about $75 for steel and brass bar and sheet stock, copper tubing, etc. A Bassett-Lowke pressure gauge is the only commercial part he uses. The locomotives weigh from 70 to 85 pounds, including the tender. His Hudson weighs 55 pounds without tender and develops a drawbar pull of about 12 pounds, more or less. Wet or rusty rail is more slippery than dry, bright rail.

The engines operate at steam pressures of 80 to 110 pounds. Fire is started with gasoline-soaked charcoal. After this is burning, pea-size bituminous coal is used for fuel. It is put into the firebox by a miniature shovel. Pistons are lubricated by an oil pump powered by the valve motion.

Most live steamers use an automobile tire pump for forced draft to get steam up. Bill and his crony, Wally Ribbeck, save their energy by using pressure obtained from Wally's Nash by removing a spark plug and attaching a hose that reaches to the locomotive. When steam pressure reaches 20 pounds, the locomotive's own blower can provide the necessary draft.

A hat-full of coal will ield power for a day of operation, but the thirsty little engines need about a gallon of water per hour. Tap water is used. It is fed from the tender to the engine either by the injector, by a pump working off the front driver axle, or by a hand pump on the tender.

Prior to injection into the boiler water is pre-heated in a copper coil that encircles the smokebox interior. The engines' copper boilers are patterned after the prototype, having flues, a combustion chamber, firebox syphons, etc. The boiler is fabricated with rivets and silver solder, and is tested before use with water at twice the steam pressure it will have to withstand. Live steam at 110 pounds pressure is not to be trifled with.

Like regular model railroading, live steaming, in one or another of its ramifications, is a year-around affair. Bill does most of his construction work during the long Wisconsin winter in the workshop adjacent to his home. Summertime is primarily devoted to operation. Each Sunday (and many Saturdays) when the weather is favorable, Bill and Wally load their engines into their automobiles and head for the layout, which is on Bill's 3 acre tract of land located about 5 miles from his home.

About 500 feet of the proposed 900 feet right of way is complete. Rail consists of 1/4 inch by 1/2 inch mild steel bar installed on trestle work to permit the engineer and his passengers to ride "side-saddle" with their legs dangling.

Engine cab roofs are removed during operation to permit access to the throttle and reverse levers installed on the backhead. The engines are equipped with steam brakes which Bill rarely uses, preferring to retard or stop his engines by grabbing the trestle work with his free hand.

How fast can they go? Well, Wally has timed his Hudson at about 10 miles per hour actual speed, or about 220 miles per hour scale speed.

The pleasure of constructing a live steam engine needs no explaining to anyone who loves to build models. And the plaesures of operation? Ah, have you ever sat behind one of these chugging little iron horses and felt its powerful surge as you eased back the throttle? Ever get a good whiff of its warm, aromatic exhaust smoke mixed with fresh, hay-scented air? Ever looked own at the hypnotic driver and rod motion, or opened the firebox door to watch the tiny inferno raging?

Until you've done these things, you will really never know why a man will devote 3000 hours, $2000 worth of tools, and all his Sundays to building and operating the 55 pounds of hot, oily temperamental machinery that is know as a live steam model locomotive.

Wally Ribbeck at the controls of his Hudson. Wally's automobile furnishes blower air to start fires in his and Bill's engines until engines' blowers take over.

Photo taken at the track of William Michaels of Racine, Wisconsin and shows Walter Ribbeck of Kenosha with his fine 1/2 inch scale Hudson. From The Live Steamer, Jan-Feb 1950.