Alcohol Burner for Live Steamers

Alcohol Burner for "Live Steamers"

by

I am continually receiving requests for particulars of the alcohol burner invented some sixty years ago by my Grandfather, Victor T. Shattock, and used in his 2-1/2" -- 4-3/4" gauge steam locomotives and to enable me to reply to these inquiries and to enable other live steam friends to obtain the information I know of no better way than to get the particulars published in Live Steam Magazine.

Perhaps it is that my Grandfather had a lazy disposition, or it may be that he liked to run his locomotives with the least inconvenience. Anyway, he gave considerable thought to the matter of obtaining simple efficient firing for small locomotives. This does not sound much when you say it fast, but when applied to firing little locomotives it covers a great deal of territory.

He had been using alcohol in his locomotives for years, and like Brother L.B.S.C., he had realized that the method used in burning alcohol or methylated spirits too often resulted in grief of one kind or another. Yet the burner, or system of firing that he was looking for almost demanded that he continue to use alcohol for fuel. What he wanted was this: The burner must be easily made, easily installed and easily removed if necessary. It must be easily lighted and must be silent in operation. It must be easily controlled, that is, an engine could be left standing under steam with just enough fire to keep her hot, and when ready to go, all that would be necessary would be a slight turn of a fuel valve. The burner must be safe, no danger of explosion or other fire hazard, and must be suitable for either indoor or outdoor locomotive running. And if, as he expected, alcohol was to be the fuel, it must not be a "poison gas plant."

Someone may remark, "Well, he didn't want much, did he?" And to this remark I make a reply that he not only obtained those requirements, but accidentally obtained one more virtue, which is that the burner is semi-automatic; but we will go into that later.

Now there is no point in going into the details of experimenting and so forth, so we will be content to say that the burner was made, has been tried out on a number of 2-1/2" -- 4-3/4" gauge locomotives under various conditions, and it seems to do this business. This burner has also been endorsed very strongly by the late Mr. Lester Friend, the "old maestro." Of course there will be skeptics, and for that reason, and for the reason that some brothers may obtain some help from this article, I am showing how this burner can be made and how it should be used.

Before starting on the details, perhaps it might be well, by way of explanation, to say why such a burner was needed in the first place. My Grandfather has spent a great deal of his spare time during the last seventy-some years on the hobby of building miniature steam locomotives; however, it was only after the first forty years that he actually got down to building a 2-1/2" gauge railroad which could be considered worth looking at; the "Miniature Southern Pacific" described in detail in previous issues of Live Steam Magazine. Now if, in order to accommodate the many visitors to this railroad by running a locomotive or two as the case may be, it was necessary for you to light up a coal fire and carry out the attendant chores, the hobby, instead of being a pleasure, would probably have become very tiresome. Therefore, he had no desire to use solid fuel, preferring to operate his locomotives from the "engineer's" angle, without the necessity of worrying about the troubles of the "fireman." He could fire up a locomotive with about as much ease as lighting the gas on the kitchen stove. Necessity, therefore, was the mother of invention, if invention it was. This article is not an advertisement; the burner cannot be purchased! If you want one, you must make it or have someone make it for you!

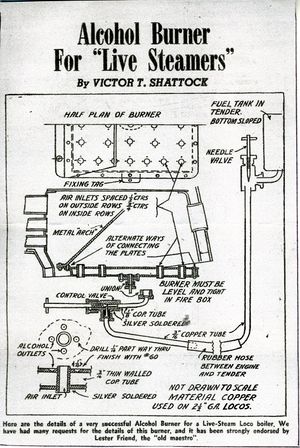

The sketch shows the general arrangement of the burner, and you will note its location in the firebox is much the same as a grate would occupy, if solid fuel was being used. The supply of alcohol is contained in a tank located on top of the tender, in the same position as the oil fuel tank of a large locomotive which uses oil for fuel.

From this tank the fuel is brought down to the burner, by means of a 3/16" copper pipe line, the connection between engine and tender being a piece of rubber hose. The control valve is placed at a convenient spot, and preferably at a point where a few inches of pipe is required to connect to the center of the under-side of the burner. No pressure other than gravity is required to bring the fuel to the burner. Denatured alcohol, controlled by a needle valve, is admitted to the vaporizing chamber. Heat for vaporizing is supplied through a copper "brick arch" which is fastened to the vaporization chamber. The vaporized alcohol leaves the chamber through tiny holes placed around inlets or nipples which admit air to the firebox. As a result of experiment the sizes of the holes and the air inlets are such that a good mixture is secured for proper combustion. It is a fact that while an engine is idle with the fire turned low, a trifle more fuel is burned than necessary, yet when in operation under a full load, which of course is the important item, the consumption of fuel is economical because the greater amount of air drawn in by reason of the increased draft produces a hotter flame. The burner consists of a flat shallow copper box. On the upper side small holes are drilled for the vapor or gas to emit, and these are located around air inlets made of 3/16" O.D. copper pipe, the inlets going right through the box. These inlets for air may be running threads and if the threads are carefully made when screwed into the box, will be found to be gas-tight, without the necessity of hard-soldering. The box can be of No. 22 gauge or even thinner copper and all joints should be hard-soldered, because during operation the burner becomes too hot for soft solder to be relied upon. The number of air inlets and the number of jets for the gas are matters for you to determine, in accordance with the conditions prevailing on your locomotive. The drawing, half-plan, shows a very efficient burner for a 2-1/2" gauge "Pacific" or similar size locomotive. A flange or boss should be hard soldered to the bottom of the box, to enable a tapping to be made for a 1/8" or larger pipe where the fuel enters the burner. In making up the burner it is a good idea to lay out and drill the air inlet holes in the plate, that is to be the top side of the burner. Use a No. 21 drill.

Then assemble the burner or clamp in place and drill the bottom plate by entering the drill through the holes already drilled in the top plate. This will give reasonable assurance that the holes are in line when the tapping is made. A 3/16"--No. 36 or 40 tap and die should be used for the threads for the air inlets. If a coarser thread is used, it may mean that you will have to hard-solder the joints on the bottom of the box to make them tight. The joints where the air inlets protrude through the top side of the box do not need to be gas-tight, as any slight leakage at this point is unimportant. Drill the hole for the fuel to enter in the bottom plate, assemble the whole with a rivet or two to hold the plates together, put in the air inlets and hard-solder. Phos-copper or sil-fos will do. The holes for gas jets may now be drilled. The sketch shows four to each air inlet, which is usually about right, but the number can be increased to five or even six if you think it necessary; However, it will be best to wait until the burner is tried out. The jets may be drilled with a No. 60 drill, or they may be drilled partly through with a 1/16" drill and the balance punched through with a needle. The holes should be uniform in size so that there will be an equal distribution of the gas. You will note the sloping piece of metal fastened to the upper front end of the burner. This serves as the "brick arch" used in large boiler fireboxes to send the flames around the firebox, and to protect the flue plate from too intense a heat. In this instance the plate serves a similar purpose and also to conduct heat to the burner itself, so that it will readily turn the incoming liquid alcohol into vapor. This arch may be made of 22 gauge copper, and should extend upwards diagonally about two-thirds the height of the firebox. It should be fastened by two or three brass screws, say 6-32 or 8-32, the heads being on the underside. This for the convenience in installing or removing the burner. Any convenient method may be used to fasten the burner to the firebox. While the burner should be level it will work if placed on the same slope as the bottom of the firebox.

I advocate the burner being level, so that any liquid fuel entering the box will be fairly well distributed, whereas if it slopes the tendency will be for any such liquid to run to one end of the box, and perhaps overflow before turning into gas. The main requirement is that the burner should fit snugly in the firebox, so that no air comes in except through the air inlets, and positively no air must enter ahead of the arch. There is an exception to the foregoing, which I believe you should make a special note of. While it is desirable that all air enter "through the inlets," it may prove that more air is required for proper combustion. This can be determined when the burner is working, by noting if it continues to give off a roaring sound and the sound disappears when the fire-door is opened. A little more air can be arranged for by permitting it to enter at the back of the burner, either by prying the burner down at the back end, or by filing off sufficient at the back and so that the fit is not so snug. It could also be taken out and two or three air inlets put in at the back with NO jets. The burner should be quiet when it is working properly. I might also point out that any air coming in at the edges of the burner will form a blanket of cold air right next to the firebox wall, and destroy some of the best convective heat transfer surface. If you have space enough, you should fit curved plates under the burner, forming a sort of bottomless, shallow ashpan. This will serve both as a sort of tuyere, and an air preheating chamber, and also tend to prevent trouble mentioned previously from air coming up past the burner and cooling the firebox walls.

The control valve is a needle valve, preferably an angle valve. The needle should not be too tapered, but rather, due to the fact that the pressure is by gravity -- and not much of that on a 2-1/2" gauge loco -- openings should be fairly free for the fuel to enter. Traps where air can accumulate in the fuel line must be eliminated. A valve should also be placed on the tender fuel tank for convenience of shutting off the fuel when the tender and locomotive is being disconnected.

It is important that a good grade of denatured alcohol be used in the burner. A poor grade will raise a terrible stink, and you'll have a real poison gas plant on your hands after all. Furthermore, if there is any water in the alcohol, this must all be vaporized in burning, and a lot of latent heat will go up the stack unused, besides lowering the flame temperature. Rubbing alcohols and such as sold by drug stores will NOT be satisfactory. Good alcohol can be purchased in gallon or five gallon cans at certain hardware and paint supply houses. Painters use it for cutting shellac.

Another precaution to observe when operating the burner is to keep the fuel line between the tender and locomotive completely clean at all times, especially since the only pressure of the fuel is that of gravity itself. Because of this lack of pressure, any foreign matter or sediment will quickly gather at the control valve and slow down, if not completely cut off, the fuel supply. It is therefore a good idea to strain the alcohol when putting it into the fuel tank. You might even consider placing a small piece of fine mesh brass screen inside the fuel tank opening to help catch any foreign particles. Years ago on a typical operating day at the GGLS track in Redwood Regional Park, some small flies got to buzzing around the bottle my Grandfather and I were using for fueling the tender. A few were overcome by the fumes and fell in. The next engine being fueled received a supply of gnats, which promptly clogged the needle valve, upsetting us considerably until we found the trouble.

It is also essential that there be draft. This applies to any type of burner, but particularly to this one. Air must be drawn in through the air inlets. Auxiliary draft is necessary to start with, a la vacuum cleaner or whatever, attached to the loco's stack. The loco should be equipped with a steam blower, so that this will be used when a few pounds of steam have been generated. To start the fire, turn on the auxiliary blower. Have a torch handy, made from a bit of steel wool wired on to a piece of rod or wire, long enough to reach into the firebox. Saturate the wool with a little alcohol, light it and shove it into the firebox. The procedure is much the same as with a gasoline blow-torch.

In other words, heat the burner with the torch and if you do not think it hot enough, "repeat the dose!" Then, before the torch goes out, turn on a little fuel at the control valve. Flame will show at the jets and the fire door can now be shut. You must now make certain that you have not turned on too much alcohol, a little practice may be necessary to ascertain the right opening for the control valve. If turned on too much there is danger of flooding the burner, where it might even overflow outside of the locomotive and start a fire, same as a gas blow-torch which spits gasoline instead of gas, when NOT thoroughly heated. You can check on the fire very easily by closing down the control valve, and if the fire goes out or dies down, you will know that the fuel is being turned into gas and all is well. If it continues to burn when the control valve is closed you will know the burner is full of liquid and was not hot enough. Let it burn until it dies down, then turn on the fuel a little at a time; the burner will probably be hot by then. When steam is up and you are using the steam-blower, you will find you can turn on the control valve a little more, until all the heat you require is obtained. The fire should burn with a blue flame, tinged with orange. If your burner is not a snug fit to the bottom of the firebox, you can stuff the cracks with a little steel wool. Make sure of your "drafting." My burners operate with the steam-blower cut down, so that it can only just be heard. The design of this burner is the result of many years' trial and error, with many rejected pieces. Alcohol is expensive, but is so clean, so easily handled, so effective, that I strongly favor it. With proper combustion, there is no reason for the alcohol burner being the unpopular "poison gas plant" that the wick arrangement is. My Grandfather's burners in all of his many locomotives, as well as my own have given us such satisfaction that I personally would like to see others try it. Especially now, since gasoline and diesel oil, et at, are harder to come by today. This burner is not recommended for any locomotives larger than one inch scale! If I have not made every point clear and you have any questions, drop me a line at home: keyrouteken@msn.com, and I will try to set you straight.

Ken Shattock

Poison Gas Plant

For the uninitiated, the "poison gas plant" reference harks back to LBSC, the British designer of small locomotives. Alcohol fired flames applied to copper produces a formaldehyde gas which, as many substances, can be lethal in adequate dosage. Its pungent odor will be objectionable if operated in an unventilated room. but NO Live Steam equipment should be fired in a closed area without adequate ventilation first provided.